‘Foresight is not about predicting the future, it’s about minimizing surprise’ according to Karl Schroeder, the Canadian science fiction and augmented reality author. Perhaps that’s what Bill Gates was trying to do in 2015 when he warned the world that it was not investing enough in preventing an epidemic1.

Whilst we might shy away from predicting a spate of major industrial incidents in the coming months, when we consider the eagerness of governments and countries to return their employees back to a ‘COVID-secure’ work place; our knowledge and understanding of human factors and behavioral safety research warn us that the perfect conditions now exist for tragic accidents to occur.

Most businesses have suffered momentous setbacks and there is an understandable eagerness to restart operations to increase productivity and earnings. However, the rush to resume quickly could mean that an essential element of risk management, human performance, is overlooked or compromised.

There have already been multiple fatalities during start up at industrial complexes around the world. To what extent these incidents were a result of new ways of working, stress and distraction is not yet fully clear but, anecdotally, we know of cases where this is happening.

The front line typically knows when deterioration and degradation in systems, processes and human performance has occurred. They can intuitively tell whether leaders are taking their safety leadership accountabilities seriously.

Human error is normal and commonplace

Organizations are heavily reliant on successful human performance to achieve their desired outcomes. Whether it is managing safety, productivity or environmental responsibility, they rely on people to apply the designed engineering and administrative processes, stick to their roles and deliver against their targets.

However, human performance does not occur in a vacuum. It is subject to influences from organizational context and primarily governed by the fundamental limitations and capabilities of the human cognitive system (i.e. our capacities for perception, attention, memory and decision-making).

Errors are normal and commonplace2. The extent of knowledge, training and level of skill has little to do with the mistakes we make. We become fatigued, our minds wander and we lose concentration. We have varying strengths and stamina, and are subject to numerous internal and external influences on performance. Moreover, a plethora of cognitive biases influences how we process information and make decisions3.

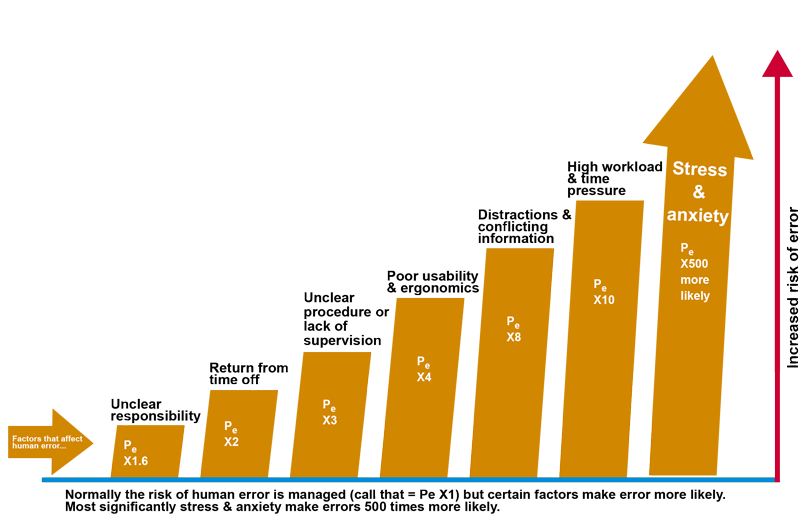

Every human error rate table tells us that people simply do not perform well if things get difficult, confusing or stressful4; conditions that will typify COVID-19 return to work. When we are stressed, we are much more likely to make errors, as much as 500 times more likely according to research on human reliability5.

New ways of working will be needed, potentially with reduced capacity. If you throw in additional complexity or variability to both routine and non-routine tasks, such as a change to the standard operating procedures (e.g. additional PPE, social distancing) or a change in personnel or supervision (e.g. due to illness or absence), then we can reasonably predict that the error rate will increase significantly – see Figure 1.

We also know from previous studies that incidents increase after a period of absence or shut-down, e.g. process safety incidents are 5 times more likely to occur at startup4, and rail drivers are twice as likely to pass a red light stop signal in the shifts immediately following time off work6. If suitable controls and adaptive capacity at the front line to deal with the foreseeable human errors are lacking, there will be an inevitable upturn in injuries, accidents and major incidents.

Figure 1: some of the factors that increase the probability of human error

Preventing a return to fatal incidents

With this foresight, how can we optimize the chances of an incident-free return to work? With an openly biased focus on human factors and psychological safety, we recommend that you consider the following actions and behaviors.

Assess, repair and upgrade organizational integrity

Assess how COVID-19 and the lockdown have affected organizational integrity. Just as the integrity of physical assets can be managed and maintained through inspection, testing, calibration and adjustment; an equivalent process can be applied to the social organization. The success with which any organization attains its goals depends on the critical interactions that occur between people, technology and processes (sometimes referred to as the people-plant-process interaction).

At all times, leaders must ensure that the sociotechnical interactions in their organizations are fit for purpose. The quality of these vital connections will influence the motivation, productivity and safety of the enterprise and exert a strong influence on human reliability.

In a rapidly changing scenario such as COVID-19, these interactions are often stressed to their limit. Weaknesses place stress on vital human interactions and significantly increase the risk of failure (see Figure 2). Organizational integrity assessment can be applied to identify the weak points and measures to compensate. When improved organizational integrity is achieved, the risk of organizational drift into failure is contained.

Figure 2: Organizational integrity factors influencing operational

Figure 2: Organizational integrity factors influencing operational

Taking a systematic approach to reviewing organizational integrity requires discipline and objectivity. In practical terms, organizations need to make sure that new ways of working are developed with human performance implications in mind. Longer term, once the potential for error has been substantially reduced, the focus can shift to optimizing performance and productivity.

In fact, this unprecedented time presents a previously unimaginable opportunity to make material changes that will not only deliver a smooth restart, but will convey longer-term benefits for safety and efficiency. Now is the perfect time to improve organizational integrity; to declutter and streamline; to fix any longstanding deficiencies in the processes and procedures that are applied in work. To simplify unnecessary complexities in the human-machine interfaces that people rely on to perform their work. To tackle any lack of openness of communications that may render sluggish the day to day change and responsiveness that is essential for an agile business.

In the past these difficulties may have been tolerated because they were thought too difficult to resolve but, over recent weeks and months, organizations have found themselves adapting and changing many work practices that had hitherto been put on the ‘too difficult’ pile. Those that have previously considered the feasibility of using novel technologies to support everyday work processes and interactions and found them too much of a challenge have recently embraced such changes rapidly.

The success of these adjustments should be garnered to make longer-term advantageous changes during the restart process. An example is a UK National Health Care Trust that prior to COVID-19 had looked into the feasibility of virtual clinics and using online methods of patient contact.

Their conclusion at that time was that it was too difficult to do without testing the technology, developing new processes and protocols, and running trials with sample groups. They decided it was a long-term, probably 10 year, goal. However, with the arrival of social distancing they had to embrace the concept and swiftly develop the necessary working methods. It has now become a part of their routine and will likely remain so as part of their new normal.

Figure 3 summarizes the critical actions leaders can take to create the conditions for safe restart and longer-term sustainable safety and performance.

Figure 3: The essential actions to protect the integrity of your organization

Embrace hypervigilance

The second strategy leaders should adopt is hypervigilance. Humans are good at responding to what is happening in the moment, being flexible and creative, and at implementing new ways of doing things. They are less good at doing things consistently or at checking and monitoring – we get bored quickly.

To overcome this and any shortcuts being taken; organizations should be doing audits, self-assessments, and video surveillance; in fact, whatever it takes to make sure that the new (COVID-19) ways of working are feasible in practice, are being followed, are not generating additional risks, and that they are being constantly improved and lessons learned rapidly shared.

Adopt mindful leadership & psychological safety

To harness successfully the full potential of your workforce, embody the principles of mindful leadership and psychological safety. Communications and workforce engagement will be essential to identify both the signals that indicate an escalation of risk and the areas of improvement that can make work more efficient and errors less likely.

Those on the frontline will know best what hasn’t been working and why there might be inefficient work-arounds. Mindful leadership is the key to unlocking the treasure trove of ideas for improvement. Mindful leaders are those who are engaged, open and welcome bad news; who embrace challenges and seek collaboration with others.

They invoke a culture in which people feel comfort admitting their mistakes, feel included in the dialogue, feel able to learn together from experience and, most importantly, feel empowered to challenge the status quo (or a new plan) without fear. Leaders play a vital role in setting the tone by inviting challenge, discussion and new ideas. By empowering and supporting people, they facilitate the changes that previously seemed too hard.

Leaders often fear that making large-scale change will be too disruptive to business and, therefore, too much of a risk. Even when the material benefits are clear to see, the road to get there might seem too long and hard. However, lockdown has imposed a halt. Everything has had to stop for a while and, as we begin to plan to restart, leaders should find the courage to make these larger changes now - to fix those long-standing problems.

To engage the energy, enthusiasm and innovation of colleagues to solve the problems we thought were unsolvable. Doing so will not only avoid mishaps during restart, but will sweep away some of the barriers to realizing better productivity and performance. People will feel engaged, listened to, and play a major role in creating their version of the new normal.

This pandemic presents us with a unique opportunity to rethink the way we work for the better. Creating a safer culture and embracing your people as a solution to be harnessed, rather than a problem to be fixed, reaps rewards not just in safety, but across all aspects of organizational performance; bringing benefits long into the future by creating more efficient, successful and sustainable operations.

References

1. The next outbreak? We’re not ready. Bill Gates. TED Talk. 2015-04-03

2. Reason, J. Human Error, 1991

3. Kahneman, D. Thinking Fast and Slow, 2011.

4. Dr David J. Smith: ‘Reliability and Maintainability and Risk’ Elsevier 7th edition, 2005

5. IEC 61511 - Functional safety - Safety instrumented systems for the process industry sector, 2001

6. Human Engineering Limited Research report for Rail Safety and Standards Board, Analysis of the May/Summer Peak in SPAD Occurrences. By Hamilton, W. I., Li, G. and Lock, D., Reference HEL/RS/02799a/RT1, 2003.

The information above is of a general nature and is not intended to address the circumstances of any particular individual or entity. Although we endeavor to provide accurate and timely information, there can be no guarantee that such information is accurate as of the date it is received, or that it will continue to be accurate in the future. No one should act on such information without appropriate professional advice after a thorough examination of the particular situation. ERM would be pleased to advise readers how the points made in this article apply to their circumstances. ERM accepts no responsibility, or liability for any loss a person may suffer for acting or refraining to act, on the material in this article.